The logics of gamification

by Jonas Kellermeyer

29.04.2025

When we think of computer games and their logics, we often associate them with pure leisure activities. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that game mechanics are also spilling over into completely different areas of life; gaming no longer only takes place in closed environments. This development is reason enough to take a closer look at the ongoing trend of gamification – or ludification – and its impact on our lives.

Game on, Game off, Game over

Wherever we look, we see playful mechanisms at work: statuses, which are rendered tangible by display bars and/or other UI elements to be filled, over so-called streaks that reward continuous use, to colorful badges that can be displayed as a badge of excellence. There are many instances of gamification to be found in different areas of today's business world.

In the following, the concept of play will be defined more broadly. Sybille Krämer (2005) offers a plausible definition: “Play is that which, in the presence of its realization, withdraws from the flow of ‘ordinary’ life” (Krämer 2005: 13). This takes into account the variety of possibilities of exact organization. The game thus opens up a fictitious reality, which, however, requires us to fully engage with it and not always emphasize the fictitious character of the structure. The spoilsport is not the one who (over)identifies with the respective context, but the one who always knows how to emphasize that the game is not reality. In other words, the one who knows how to prevent (temporary) immersion with relativizing objections. He is an individual who breaks with convention, according to which, for the duration of the game, it may very well appear to be a “serious matter”. A good actor is one who knows how to perfect the illusion of seriousness and captivate his audience, but who is (paradoxically) aware of the fiction as such.

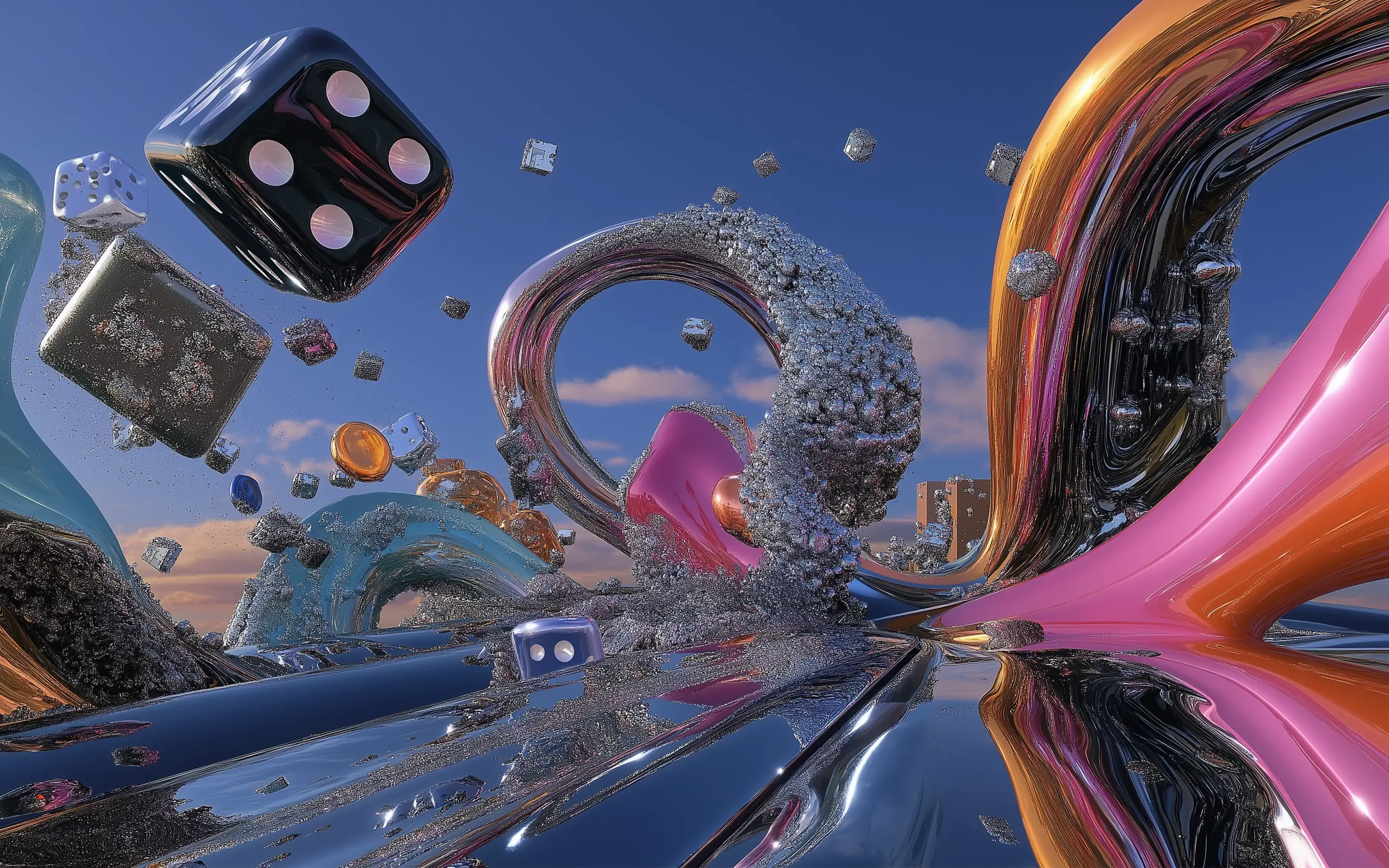

If we take this fact seriously, it becomes obvious that various game mechanics and special features in the rules play a key role in the execution of the quasi-fictional/quasi-realistic act. The dice game thrives on the stochastic randomness of the possibilities. Each number has the same probability of being rolled: Classically 1/6. As a result, the use of a dice introduces an arbitrary element into the course of the game, which does not exclude tactics, but allows an immanent contingency to manifest itself. In the best case scenario, the use of dice teaches the player something about the stochastic entropy that constitutes the world (cf. Serres 1998).

The word fiction already denotes something made, a construction, which links it to the overused concept of facts. The game succeeds when the respective rules begin to materialize intersubjectively. In other words, when the world of the adversaries or collaborators begins to contract selectively and – together with its meaning – begins to condense against the yardstick of the set of rules. It becomes particularly interesting when other goals are considered desirable in such a context than is the case in the (“profane”) world of life. In the context of the game, this fact can be used to make scenarios such as the Risk game palatable to people who generally have no interest in imperialist ambitions. So if the (subjective) assumptions that are otherwise considered fixed are deliberately broken and the participants in the game do not classify them as unreasonable, then it is sometimes possible to create a gaming experience in which challenge – in many respects – becomes the leitmotif.

Games promise to establish a structure that can have a positive impact in terms of productivity. In order to delve a little deeper into the matter, we would like to take a closer look at this expedient dynamic that unfolds in the game in the following section.

About structured rules and regulatory structures

If one understands play as a mode in which (free of worldly consequences) one can practice or in which character traits can be tried out and sometimes consolidated, then it becomes obvious that the applicable rules of a particular game have more than just an immanent quality, but rather bear witness to an importance for the individual's existence. It appears to be a logical consequence that such an identity-forming activity can and must take different forms depending on the socio-economic/cultural differences of the observed (and continuously observing) individuals.

For example, the Roman historian Tacitus notes in his opus magnum “Germania” that the Germanic tribes, who were considered barbaric, indulged from time to time “strangely sober” in dice games, which they pursued as a serious activity. According to Tacitus, they made up for the absence of substance-based intoxication with a veritable gambling frenzy: “in winning and losing [they] are so unrestrained that, when they have nothing left, they use their freedom and person in the last throw”. This proto-religious fury seems to be a key feature of the mental predisposition of the dice game. All or nothing, that is ultimately in the (metaphorical) hands of fate. And that is exactly where it should lie. It is important that the probability of winning can be calculated quasi-rationally, but at the same time there is never 100% certainty.

The situation is completely different with tactical games such as chess. This is much more akin to warfare, which - not without some cynicism - can itself be understood as “playful”. However, a figure of chance also appears in chess: “‘Ribaldus’, actually the pawn in chess, is considered synonymous with the player. His attributes are three dice, which he throws into the air with his left hand. A sign that he is ready to play” (Näther 2014: 6). This playing piece offers a kind of entropic passe-partout for the clearly structured tactics that are actually the focus. Since the pieces in the game of chess ultimately reflect social realities, the pawn can be seen as a fateful figure whose power lies in the homogeneous mass, far removed from individualization. “It symbolizes a marginal figure in society” (ibid.) and, from the perspective of the tactical commander, has no relevant individual characteristics, which is why it always finds itself in the front line as ‘cannon fodder’. The importance of the pieces is also reflected in their absolute number: eight pawns, two rooks, two knights, two bishops; only one queen and only one king, which must also be protected. As a strategist removed from the implicitly warlike events, the chess player mimes the highest link in the (military) hierarchy for the duration of the game, which is why it can be assumed that chess developed in a hegemonic atmosphere - “the Emperor of China played it” (Deleuze & Guattari 1992: 483). With rank comes responsibility: “fate” and/or “luck” are concepts that have no place in the context of chess.

The prominent emergence of so-called “playrooms” (especially in the bourgeois world of the 19th century) testifies to the strict separation of spheres within the developing hegemony. Play is assigned an explicit space, as are work, eating, sleeping, etc. This rigid separation goes hand in hand with the perception that everything that takes place outside or within a designated space also requires a corresponding mindset. A gathering in a salon is therefore essentially different from one in a casino and ultimately has a fundamentally different character to a meeting in a study. It is precisely this bourgeois-differential character that is responsible for the development of something like an explicitly location-bound gambling addiction (as described in Dostoyevsky's “Gambler”, among others).

From the playroom to everyday life - the triumph of gamification

In the recent past in particular, we have observed a downright profanization of playful elements: The directed access to the nature of a “Homo Ludens” (1956) as claimed by Johann Huizinga is a seemingly worthwhile undertaking that promotes increased involvement as well as providing concise explanations for demonstrated behaviour. Through playful intervention, it is becoming increasingly possible to actively influence people and their behavioral patterns. Nudging, for example, is a type of control regime related to gamification, where the aim is to induce desirable actions through appropriate incentives, but never to refer directly to the goal. The side effects of the playful actions are ultimately the truly important aspects that the actual goal was to produce. Through clever distraction, the apparent waste products of acting subjects become the truly valuable facts.

Even if a view such as that put forward by Johan Huizinga in his work Homo Ludens: a study of the play element in culture, that the phenomenon of culture is first created by play because it is “older than culture” (Huizinga 1956: 9), seems to be too far-fetched, the psycho-social implications that go hand in hand with play should be taken seriously and considered in relation to cultural development. Especially as a training ground where the individual can test assumptions about the world free of consequences, play can and must be given an ever-increasingly important role in terms of the perceived world.

Literature

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Félix (1992): Tausend Plateaus. Kapitalismus und Schizophrenie II. Merve Verlag, Berlin.

Huizinga, Johan (1956): Homo Ludens. Vom Ursprung der Kultur im Spiel. Rowohlt Verlag, Hamburg.

Krämer, Sybille (2005): “Die Welt, ein Spiel? Über die Spielbewegung als Umkehrbarkeit.” In: Hantje Cantz Verlag (Hg.) Spielen — Zwischen Rausch und Regel, S. 11-17.

Näher, Ulrike (2014): Zur Geschichte des Glücksspiels.

Serres, Michel (1998): Die fünf Sinne. Eine Philosophie der Gemische und Gemenge. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt a.M.

About the author

As a communications expert, Jonas is responsible for the linguistic representation of the Taikonauten, as well as for crafting all R&D-related content with an anticipated public impact. After some time in the academic research landscape, he has set out to broaden his horizons as much as his vocabulary even further.